Laurie A. Buonanno (June 26, 2024, Updated November 1, 2025)

“My feeling was that Rocky was less a liberal than he was a Baptist. He was acting out of personal conviction rather than out of liberal ideology. In fact, I found him to be totally impatient with ideological notions, even impatient with constitutional questions.” – Jack Germond, quoted in “Benjamin, G., & Hurd, T. N. (Eds.). (1984). Rockefeller in Retrospect: The Governor’s New York Legacy. Rockefeller Institute of Government, p. 58.

Introduction

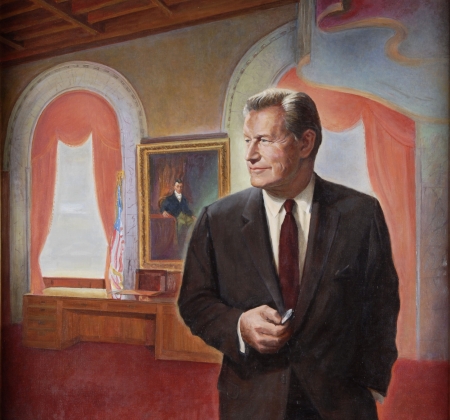

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, New York State’s governor from January 1, 1959-December 18, 1973, has often been blamed for setting New York State on a path of profligacy that would eventually take the State and NYC to the edge of bankruptcy in 1975. Rockefeller’s detractors described him as a spendthrift governor inconsiderate of the long-term spending implications of his programs, attributing his motives to his desire to win the Presidency.

Rockefeller’s admirers counter that he arrested New York’s downward slide and left a priceless legacy of programs and infrastructure that lived up to the State’s moniker – the Empire State. Rockefeller was sworn in as New York State’s 49th governor in January of 1959, but to a state in decline. While still the most populous state, California (14 million) was closing in fast on New York’s 16 million (overtaking New York in November 1962). New Yorkers hated losing a status it had so long enjoyed, but this was nothing compared to the creeping crises lurking just around the corner. The most daunting challenges were deindustrialization and lack of foresight and leadership among New York’s policymakers in failing to build a public higher education to meet the needs of the mid-to-late 20th and 21st century economy.

New York’s manufacturing sector had been experiencing an absolute decline since the mid-1950s with the service sectors and high-tech production not yet compensating for the loss of manufacturing jobs.[1] New York State lost two million jobs between 1960 and 1974; NYC, alone, lost more than 600,000 industrial jobs between 1960-1975. Between 1954-1960, New York State had dropped to dead last among the states in investment per worker in new plants and equipment, while California surged ahead in aircraft, electronics, and automobile manufacturing (McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981, p. 33 & 36). Throughout his tenure, Rockefeller attempted to use the power of the State–such as lower corporate taxes and tax incentives–to keep manufacturing competitive and to staunch its exodus to the Sunbelt and to help New York’s industries to modernize its deteriorating industrial base.

The second problem, public education, was intimately tied to the first. Rockefeller instituted generous transfers to local government to strengthen elementary and secondary education, and, of course, his greatest legacy was the State University of New York (SUNY), “a strong higher education system (that) would enable (Rockefeller) to retain and attract business and industry to the state” (Glazer, 1989, p. 3). The creeping crisis Rockefeller faced when entering his first (and as it turned out, his only) elected office in 1959 was that baby boomers would be graduating from high school in unprecedented numbers when more families could afford to assist their children with four years of lost income, more students expressed interest in post-secondary education, and the State needed a more educated workforce as it transitioned to higher tech manufacturing and the service economy.[2] Another factor that continued to put pressure on enrollment was the postwar (1948) enactment of the GI Bill, a program that at the time provided free college education to veterans (Glazer, 1989, p. 6). Indeed, Governor Dewey had established SUNY in 1948 mainly to demonstrate that New York was being considerate of its veterans’ needs, but Dewey and the next governor (W. Avrell Harriman, a Democrat) did not prioritize investing in SUNY.

In 1959, there were 401,000 full- and part-time enrollments in NYS colleges and universities. The number of New Yorkers hoping to attend college was predicted to increase exponentially: 425,000 (1960), 646,000 (1965), 804,000 (1970), and 962,000 (1975) (Committee on Higher Education/Heald Commission, 1960, p. 3). Only 38 percent of college students in New York were enrolled in public colleges and universities compared to 80 percent in California (Heald Report, 1960, p. 6).[3] New York was also underinvesting in public higher education: California was spending $15.17 per capita of its tax dollars on public higher education compared to $5.41 in New York (Committee on Higher Education/Heald Commission, 1960, p. 45).

As a consequence of the State’s neglect of higher education, which was largely an attempt to protect its many private colleges and universities from public sector competition, the estimated outmigration of New York’s undergraduates was 26 percent of the total New York State undergraduates (1958 figure)–a massive brain drain because many of these young people could be expected never to return to the Empire State (Committee on Higher Education/Heald Commission, 1960, p. 55). At the same time, the public universities of other states could no longer be counted on to absorb the exodus of college-bound New Yorkers because states with good public university systems were beginning to impose “tighter restrictions on the admission of out-of-state students.” (Committee on Higher Education/Heald Commission, 1960, p. 54). Astoundingly, those same New York private colleges and universities lobbying against funding a good higher public education system did not have the capacity to absorb the increased demand from baby boomers and veterans. In the meantime, SUNY was turning away thousands of applicants in the late 1950s due to a “severe lack of space” (State University Construction Fund, nd). There was yet another important factor why New York needed a good public higher education system. Private institutions were discriminating against Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Catholics, and Jews.

The Heald Commission (1960) also estimated that between 1960-1975 New York would need to educate over a million workers to meet the needs of professional and technical manpower alone. Consequently, Rockefeller made public higher education a centerpiece of his 1958 campaign, pitching it partly as New York’s contribution to the perception of a national emergency that arose from America’s shock over the Soviet’s launching of Sputnik I. The prospect of the Soviets racing ahead of the Americans had deeply affected Rockefeller–an unrepentant Cold Warrior– as it had many Americans, culminating in Congress passage of the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958.[4] When, as one of his first actions as governor, Rockefeller established a task force to examine the higher education system in New York and provide concrete proposals for reform, the Heald Commission’s report (1960, p. 9) confirmed what most New Yorkers already knew: public higher education in New York was “a limping and apologetic enterprise.”

Of course, New York faced many other problems that had been either tackled on a piecemeal basis or completely ignored. Roads were becoming increasingly congested and policymakers were belatedly realizing no amount of new road construction would alleviate congestion, especially in greater New York City (see Caro, 1975). Public transportation desperately needed state investment–the Long Island Railroad offered a slow, miserable commute for the largest suburban population on earth, the Upstate cities of Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo could not afford adequate public transportation, and NYC’s subway system was deteriorating and unreliable. With an estimated gap of 500,000 housing units along with a deteriorating housing stock in cities throughout the State, there was also a dire need for affordable housing for low- and middle- income households. The state’s mental health facilities were dangerously overcrowded. Water pollution was rampant. Lake Erie was “dead,” the Hudson River was laden with PCBs, when the wind blew from Rochester, beaches to the east were closed, and the NYS Department of Health warned children and women of childbearing age not to eat the fish from New York State’s waters. New York State (along with other parts of the Northeast) had been experiencing periodic blackouts and brownouts due to an antiquated and overextended power grid.[5] New York’s parks system was disorganized and unregulated development was robbing New York of its natural beauty.

It would take an exceptional governor to comprehend the interrelated nature of these creeping crises, let alone implement policies to address these crises. It would also require a leader who could articulate solutions to the electorate and bring them around to convince a “constitutionally Republican” legislature dominated by tight fisted Upstate Republicans and a cohesive block of Nassau County conservatives that the State government was the only entity capable of effectively tackling these crises.[6]

At the same time, Rockefeller was dismissive of the labels “conservative” and “liberal” and liked to think of himself as a “doer.” In his Godkin Lectures on the subject of American federalism, Rockefeller (1962, p. 19) derided timid leadership that “passively awaits the high noon of crisis.” Resolving these interrelated creeping crises before they reached crisis proportions would cost money and lots of it. The question for Rockefeller was whether the current revenue-generating capacity of the State was up to the task.

Getting Things Done

Governor Harlod Levander of Minnesota, having met Rockefeller, observed, “Once you have met him, you can no longer say that this is an age without great men” (related by Richard Rosenbaum in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 64). And it is true, Rockefeller did great things for New York State. (Box 1 contains a summary of Rockefeller’s major achievements.) Furthermore, some of Rockefeller’s legislative initiatives were later adopted practically in toto by Congress and his programs were so ahead of their time that no federal funding existed. (The consequence was that when the federal government “caught on,” New York paid the price for innovation in not qualifying for federal funds.) Legislators knew the public generally supported Rockefeller’s programs and that the electorate re-elected him even as they criticized him. In early 1966 when Rocky was gearing up his campaign to run for a third term, a consultant told him he couldn’t be re-elected as dog catcher. Yet he went on to win that election by 392,263 votes.[7] As Jack Germond observed, Rockefeller was a good fit for the New York electorate because “he was a little outrageous and a little brash.” And if he was a rascal, “he was our rascal…” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 54).[8]

Box 1 Nelson A. Rockefeller’s Legacy in New York State

| Energy & Transportation Transit authorities exempted from Public Service Commission regulation (Benjamin & Hurd, p. 268), Job Development Authority (1962), Long Island Railroad (purchased for $65 million using a first instance appropriation), Metropolitan Transit Authority (1965), Robert Moses’ Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority absorbed by MTA (1967), Niagara Frontier Transit Authority/Rochester-Genesee Regional TA (1969), Central NY TA (1970), Capital District TA (1970), Transportation Construction Fund (in 1982 was still the largest single construction program of a public nature in the history of the US) (Zimmerman in Benjamin and Hurd, p. 101), Extended NYS Thruway, Southern Tier and other expressways to connect Upstate to Downstate and the Midwest, New York State Atomic Energy Authority (precursor to NYSERDA) Education & Culture New York State Council of the Arts (first such council in the US, became the model for the National Endowment for the Arts (1960), State University Construction Fund (1962), Dormitory Authority expands to allow private campuses to engage in low-interest borrowing, Consolidated CUNY into a system- CUNY grew from 7 campuses to 20, Consolidated SUNY into a system, SUNY grew from 46 campuses to 64 campuses, New SUNY campuses – Albany, Alfred, Binghamton, Canton, Purchase, Utica/Rome, Old Westbury, Stony Brook, University at Buffalo North Campus, Higher Education Assistance Corporation (low interest student loans and no interest accumulation while in school) (1961)-since 1974, part of the New York State Higher Education Services Corporation, The Scholar Incentive Program (precursor to the Tuition Assistance Program, estb. 1974) (1961), Support for private colleges & universities (e.g. Bundy Aid), State aid for disabled children Public Health & Safety/Consumer Protection Laboratory Inspection Law (adopted almost word for word by Congress), Expanded medical research capacity throughout NYS, Required seat belts in cars, First State consumer protection board, Consumer fraud office in the Attorney General’s Office, No-fault auto insurance, Truth-in-lending law, Three-day period for consumer to cancel a door-to-door sales contract, Meat & poultry inspection, Out-of-state land promoters under State supervision, Mail order insurance companies under State supervision Labor Public sector collective bargaining, Established NYS’s statutory minimum wage with regular increases Environmental Conservation Department of Environmental Conservation (1970), Water treatment plants, Expansion of Adirondack State Park and placed under land use control (the largest tract of land in the US where development was controlled) Housing & Employment Job Development Authority (1962) dba Empire State Development Authority, Housing Financing Agency (1960) (by 1982 had been copied by over 40 states as well and many countries and regions) Infrastructure Urban Development Corporation (1968) dba Empire State Development CorporationSouth Mall (Empire State Plaza) Albany Reform Raised salaries of state workers, Reorganization of the executive branch, Reorganization of the state-court system Sources: (Author compilation, primarily from Benjamin & Hurd, 1984; Glazer, 1989; Smith, 2014; United States. Congress. House. Committee on the Judiciary, 1974) |

Paying for Progress

Turning around the Empire State was an expensive proposition. New York State’s annual budget grew from $1.79 billion to $8.3 billion during Rockefeller’s 15-year tenure (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 73).[9] Edward Kresky – who had held various high level posts in the Rockefeller administration – reflected on Rockefeller’s first campaign in which he portrayed Avrell Harriman, a Democrat, as a spendthrift executive who had run up an $850 million budget deficit (it was actually $400 million) (Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 196; Smith, 2014). In Rockefeller’s first budget message – breaking tradition by addressing in person a joint session of the Senate and Assembly – he pledged fealty to pay-as-you-go and promised minimal bond financing.[10] During his first term of office, however, Rockefeller began to appreciate why Governor Al Smith once quipped, “You don’t pay and you don’t go” (quoted by William Ronan in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 271). By the “beginning of his second term…he was prepared to spend lavishly to improve State government” (observation by Hollis Ingraham, First Deputy Commissioner of Health, 1959-63, Commissioner of Health, 1963-74) (Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 39).

Rockefeller’s tenure as New York’s governor coincided with the Lyndon B. Johnson administration and the Great Society. The two men enjoyed a close working relationship and Rockefeller was his most enthusiastic governor in the implementation of Great Society programs. Although Rockefeller’s embrace of Great Society programs may seem surprising to the contemporary reader, it made sense. Middle- and upper-income New Yorkers were moving to the suburbs and leaving lower-income families (who in many cases were new to New York–African Americans from the South seeking jobs and freedom from Jim Crow laws and Puerto Ricans escaping severe poverty on their island territory) to populate the cities middle-income New Yorkers were leaving behind. Rockefeller needed to ensure the new city dwellers had access to decent housing and affordable health care, good (local) educational opportunities for their children, and food for their tables. Whether generous social benefits actually attracted more impoverished individuals from the southern states and Puerto Rico to the more generous New York as was often claimed even by Rockefeller (see Rockefeller, 1971, p. 329) has never been definitively answered. Nevertheless, Republicans branded New York a “welfare magnet” during Rockefeller’s tenure–and Republicans blamed Rockefeller for New York’s generous social welfare benefits.[11]

Throughout his administration, Rockefeller struggled to balance liberals and conservatives in the unique milieu that was New York. Rockefeller, above all else, was pragmatic: he recognized his unique brand of Republicanism, once describing himself as having “a Democratic heart with a Republican head” (Smith, 2014, p. xxxiv). So, for example, while Rockefeller the man with a Democratic heart sought to ease the suffering of destitute New Yorkers by building new low-income housing, adopting a generous Medicaid and welfare (AFDC) package, Rockefeller the Republican established the Office of Welfare Inspector to, as he explained “to separate the needy from the greedy” (quoted by Malcom Wilson, in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 21).[12]

Unquestionably, Rockefeller was a pioneer in implementing the Great Society experiment with health care for the poor. Indeed, New York had also figured out how to get more money to support Medicaid than other states – triggering Congress to “pull back some of the law,” and according to Rockefeller “to keep New York from getting so much money” (Nathan, 2008). Yet New York was also, in hindsight, a bit too eager about agreeing to Great Society programs. The Legislature, for example, held just a one-day hearing on the Medicaid bill. It “sailed through both houses of the state legislature” after the “executive office warned the legislature that failure to approve the bill would result in New York State’s loss of from $6 to $7 million a month in federal aid” (McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981). The original legislation covered about one-third of New York’s population! Thus was the beginning of a long history of New York scheming up new ways to “game” Medicaid; in turn, Democrats in Washington led by LBJ had “gamed ” New York because Medicaid was a far more expensive program than Congress and the states had envisioned. The cost of Medicaid increased from $606.7 million in 1967 to $2 billion in 1973 (Barrett, 2022, p. 355). As McClelland and Magdovitz (1981, p. 190) put it, “The aid program that was initially lavish to the point of idiocy was subsequently cut back to being merely generous.”

The constitutional sources of financing for the state government are taxes, fees, and full faith and credit bonds.[13] (See Box 2.) Three developments convinced Rockefeller he could not depend on traditional sources of financing. First, voters did not always approve bond referendums. Second, the voters rejected Rockefeller’s request to change the Constitution to allow SUNY to borrow for capital construction. While Rockefeller could try again in two years (a constitutional amendment must be approved by two consecutive legislative sessions before being presented to the voters) Rockefeller had (correctly) recognized the creeping crisis of public higher education: he was in a race against a demographic time bomb. And, third, Rockefeller (1971, p. 329) recognized that New York was reaching its taxation limit, writing “any further substantial increase in taxes in New York is going to drive out its job-producing, revenue-producing industries, and the individuals who pay high income taxes.”

Box 2 Financing Rockefeller’s New York from Traditional Sources

| Taxes & Tax Incentives increased taxes eight times higher taxes on personal income taxes (with three top brackets added),decreased corporate income taxes sought more aggressive depreciation allowances for new and expanding industries, introduced State sales tax of 2% in 1965; raised to 3% in 1969, increased taxes on gasoline, cigarettes, and estate Bonds (full-faith and credit, required voter approval) $912 million in 1959; $3.4 billion when Rockefeller left office in 1973, 1959 – middle-income housing, 1961 -voters rejected a higher-education bond for the fourth time, which triggered Rockefeller to establish the State University Construction Fund in 1962 financed with bonds sold by the Housing Finance Agency (HFA), 1965 – $1 billion Pure Waters, 1967 – $2.5 billion Transportation (mass transit & highways) (the record at the time), 1959-1964 – $4.6 billion to acquire parklands, 1965 voters rejected bonds to finance low-income housing for the fifth time, which triggered Rockefeller to establish the UDC in 1968, 1971 voters rejected $2.5 billion bond issue for transportation, 1973 voters rejected $3.5 billion bond issues for transportation Constitutional amendments voters approved allowing the state to guarantee the borrowing of Port of New York Authority and the Job Development Authority, voters rejected allow the state to guarantee borrowing of up to $500 million for SUNY construction Table sources: (Connery & Benjamin, 1979; Glazer, 1989; McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981; Representatives, 1974; Rubenstein, 1992; Smith, 2014) |

Innovative Financing

Unlike FDR’s New Deal or LBJ’s Great Society, Rockefeller did not have access to the federal government’s printing press – he was constitutionally required to balance New York’s annual budget.[14] Rockefeller found ways around the constitutional requirement of asking the voters’ permission to borrow. He did so through public authorities and the issuance of moral obligation bonds, lease purchasing, and first-instance appropriations.

Public Authorities and Moral Obligation Bonds. Public authorities and public benefit corporations are quasi-governmental agencies established through a special act of the NYS legislature (NYS Constitution, Article VII State Finances, Section 3). Public authorities can hold real estate and they can issue debt, but they do not have taxing authority. Therefore, they derive their revenue from “user charges, fees, tolls, and revenue bonds” (Henderson, 2012, p. 205). Significantly, because public authorities are tax-free securities sold to investors in the municipal bond market they offer a tax-free investment vehicle for those who pay New York State taxes.

Public authorities had become a method to circumvent the constitutional prohibition of issuing debt without the voters’ approval long before Rockefeller became governor. But to describe the public authority as somehow hoodwinking the voters is an unfair assessment of the public authority and perhaps underestimates the polity’s understanding of their purpose. The Port Authority, established in 1921, was NYS’s first public authority. Progressives supported the Port Authority’s management structure because it would “insulate the public’s business from overt political pressures” thereby professionalizing public management, but also ensuring that the authority’s long-term planning would not be harmed by the short-term interests of politicianhad actually pioneered the PA concept a hundred years earlier in its financing of the Erie Canal.) Robert Moses took the public authority to a new level with his Triborough Bridge Authority, which more than paid for itself in tolls (Caro, 1975). Governor Dewey established the New York Thruway Authority as another self-sustaining public authority. Indeed, Republicans and Democrats had established and defended public authorities, but always as self-sufficient revenue-generating entities

During the 1938 Constitutional Convention, the delegates debated banning and/or restricting the power of public authorities. The former governor Al Smith, a delegate, argued that severe restrictions would “paralyze the one method we discovered of getting work done expeditiously” (quoted in Galie, 2016, pp. 144-5). By 1938, when voters approved a constitutional change that required a special act of the Legislature to establish a local or state public authority (Article X, Section 5) there were already 40 public authorities operating in the Empire State and by 1956 there were 64 (Lachman & Polner, 2010, p. 80). Between 1921 and 1958, the Legislature created more than 60 public authorities (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 226). Unlike the full-faith-and-credit of bond issues approved by the voters, public authority borrowing constitutes a “moral obligation debt” since a 1938 amendment to the New York State Constitution includes a clause that the State “shall” not be liable for debt obligations incurred by a public authority).[15] (The moral obligation bond was the brainchild of a Wall Street attorney–John Mitchell– who was destined to become Richard Nixon’s Attorney General. MItchell invented the concept when he was an attorney with the law firm of Nixon, Rose, and Mudge.)[16]

Under Rockefeller, the Housing Finance Agency (HFA), which provided the financing for SUNY construction, issued the first moral obligation bond in the nation (Greenhouse, 1975). Before long, public authorities became multi-purpose behemoths whose projects were financed with massive bond indebtedness, especially those such as the Urban Development Corporation (UDC) that issued bonds based on receipts projected far into the future. When Rockefeller asked the Legislature to authorize the UDC to issue a $1 billion revenue bond he assured them, “As these bonds would be self-liquidating, this program could be carried out without any increase in state or municipal debt or cost to the taxpayer” (quoted in Greenhouse, 1975).

Importantly, New York under Rockefeller revived the ability of states to do “big things,” an ability of which they had been deprived when states amended their constitutions to forbid the use of public funds for private use (read, railroads) and/or required voter approval to incur debt (Colman, 1974, p. 74). In bill after bill, year after year, the State Legislature approved Rockefeller’s requests to establish new public authorities. Naturally, Rockefeller claimed that users would repay the public authorities: student tuition would finance the State University Construction Fund (SUCF), rents would finance the HFA and the UDC, and fares would pay for the MTA. Of course this was complete fiction, because student tuition was far too low (and it was borrowing from Peter to pay Paul because SUNY students received state financial aid), rents never covered the costs of projects financed by the HFA and UDC, and fares never covered the MTA’s expenses. In fact, the UDC received “endless state support almost from its inception, much of it to cover operating expenses” (McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981, p. 239).

Nearly is the key point here, because when bankers tested the State’s commitment to their moral obligation when they cut off funds to the State’s biggest public authority, Governor Hugh Carey and UDC newly appointed EDC Chair, Richard Ravitch, worked with bankers and the state legislature’s leaders to bail out the UDC and send it on the path to solvency (Lachman & Polner, 2010).

Lease Purchasing. It is often difficult to separate lease purchasing from the public authority, but there are various ways in Rockefeller used leasing to circumvent voter approval for capital projects. As with public authorities, Rockefeller did not invent lease purchasing. The practice dates to the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York (DASNY), which Governor Dewey signed into law in 1944 to provide financing for the construction of dormitories at the eleven state teachers’ colleges (DASNY, nd).[18] While the idea of leasing (in 1954 DASNY began leasing the dorms it financed to SUNY) pre-dated Rockefeller, unquestionably he broadened DASNY’s mission to provide financing to construct dormitories at private universities (1960), finance and construct hospitals with nursing schools (1964), and finance new construction at CUNY (1966). Therefore, Rockefeller changed the notion of a public authority as financing and operating a specific entity (such as the NYS Thruway authority or canal authority) to one that could serve the public interest more broadly. DASNY, for example, grew from an agency that financed and built SUNY dormitories to “one of the largest financiers and builders of social infrastructure in the United States,” managing a portfolio of 1000 construction projects in 2022 (DASNY, nd). Much of the criticism of lease purchasing “gimmickry,” however, was reserved for the South Mall (later renamed the Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza), which Rockefeller–betting New York’s voters would turn down a bond request–was able to finance construction by working with Albany’s Mayor Erastus Corning who issued Albany County bonds. The State paid for the principal and interest as “rent,” to the county, with the State taking ownership in 2001 once the bonds had been paid. Rockefeller’s administration also perfected the lease purchase as a budgetary balancing mechanism. Was the budget really balanced when the state agency “sold” a building to a PA and then “leased” it back, paying annual “lease” payments through budgetary appropriations?

First-Instance Appropriations. Many of the new pubic authorities needed funds to get them off the ground, which Rockefeller asked the Legislature to authorize as “first-instance appropriations” (in essence, “start-up” money). A good portion of the first-instance appropriations were never recovered: between 1964 and 1972, only about 15 percent ($63.1 million) had been repaid by mid-1972 and one-third ($154.1 million) had been written off, with $87.2 million of the forgiven appropriations made to the MTA (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 219). Yet it is difficult to argue that these first-instance appropriations somehow squandering taxpayer’s dollars. Afterall, first-instance appropriations were used to purchase the LIRR for $65 million and build SUNY’s dormitories (see above).

Unanticipated events that led to financial difficulties

The 1975 NYC fiscal crisis was not an isolated incident, but rather intimately connected to the fiscal difficulties with which the State was struggling during the stagflation of the late 1960s and into the mid-1970s. From 1958-1964, the US experienced modest inflation (1.2 percent per year), but in 1965 inflation began to climb (U.S. Congress, House Hearings, 1974, p. 3). Rockefeller found it increasingly difficult to pay for state initiatives, generous fiscal transfers to local governments (especially for schools), while meeting Great Society social welfare programs designed to be delivered through federal-State co-financing (Medicaid, AFDC, and low-income housing). Consequently, Rockefeller blamed the 1971 state budget crisis on the Local Assistance Fund (to pay for locally delivered services, particularly Medicaid) – to the tune of 63¢ of every tax dollar (Barrett, 2022, p. 355) and sought federal help to balance the budget.[19]

What had happened? By 1970, the country was in a recession with 6 percent unemployment, but accompanied by high inflation (stagflation). As is often the case with economic downturns, New York took a big hit or as Hugh Carey was later to observe, “The Northeast was suffering from a common cold, but New York had a case of pneumonia.” A temporary reprieve for the economy in late 1971 was cut short by price increases in the middle of 1973. The Arab embargo of oil to the US (October 1973) sent prices (and interest rates) soaring. Richard Nixon was re-elected in a landslide in 1972 and on January 6, 1973 Nixon suspended half the laws that dealt with housing and urban renewal in the U.S. (Benjamin and Hurd 1984, p. 211). The Housing and Urban Development Agency (HUD) “declared a moratorium on federal subsidies crucial to the financing of most of UDC’s residential projects” yet UDC had been “building based on expectations of continued federal subsidies” (McClelland & Magovitz, 1981, p. 237). From November 1973 through 1975, the US experienced the worst downtown since the Great Depression. Rockefeller, it seems, while simultaneously tackling the crises of higher public education, affordable housing, the relocation of poorer Americans to New York, and spending on quality of life (e.g. innovative environmental policies, arts and culture) had not sufficiently planned for a rainy day.

Certainly, a crisis, with the right ingredients of leadership talent and luck can create a better society for its citizens; on the other hand, crises are also dangerous for a government’s fiscal health and can have devastating consequences for the polity. Declaring himself “free,” Rockefeller resigned from the governorship in December 1973, ostensibly to chair the The Commission on Critical Choices for Americans (CCCA) (originally “America in the Third Century”) a bipartisan panel proposed by Richard Nixon with great fanfair in May of that year and an outgrowth of Rockefeller’s earlier announcement to “undertake a major inquir into the role of the modern state in our changing Federal system” (Narvaez, 1973; Time, 1973). Of course, most observers at the time saw it as Rocky’s last chance to demonstrate to the American public why they should vote him into the White House. Malcom Wilson, his long serving Lt. Governor, was left in charge to deal with the complex edifice Rockefeller had built, and worse yet, he did not have personal relationships with Wall Street bankers as had the scion of one of America’s wealthiest families and older brother to Chase Manhattan bank’s CEO (David Rockefeller). These personal relationships were certainly a factor in Rockefeller’s success with persuading banks to underwrite, invest in, and market moral obligation bonds.

When Hugh Carey, a Democrat, returned to Washington as New York’s governor to plead for federal help to keep NYC and NYS solvent, Rockefeller–now vice-president–quipped “I drank the champagne. You have the hangover” (quoted in Lachman & Polner, 2010). As it was to turn out, New York was fortunate that Hugh Carey was no neophyte in D.C.; in fact, when he was a congressman, one observer described him as the “de facto” leader of NY’s congressional delegation (Peirce 1972, p. 59). Cary had also been a member of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.[20] When he arrived in Albany, Governor Carey confronted a complex web of financial arrangements bequeathed by Rockefeller. An exasperated Carey commented, “In New York State, we haven’t found only back-door financing, we’ve got side-door financing. And because of New York’s borrowing over the years–through state government, its authorities and agencies, and UDC and MTA–we got money going out the doors, the windows, and the portholes.” quoted in Lachman & Polner, 2010, p. 81).

Rockefeller’s Legacy

Rockefeller’s identification and tackling of crises is a complex story to unwind because in the first decade of the 15-year Rockefeller administration New York benefitted from a strong economy and low interest rates, enabling state policymakers to undertake a major expansion of its social (schools, universities, hospitals, mental health facilities) and transportation infrastructure (mass transit and highways). Neal Peirce (1972, p. 298), who in this time period wrote an influential book examining US “Megastates,” concluded that Rockefeller, “built the most socially advanced state government in United States history.” The consensus at the time was that without federal monies–which were not forthcoming–the “Empire State” would become a phrase that invoked the State’s former glory. Disagreements about Rockefeller’s legacy, it seems, can only be settled in terms of whether New Yorkers wanted the services and projects Rockefeller provided. The prima facie answer has to be “yes” because voters continued to re-elect him knowing full well that nothing was for free. But that begs the question–did Rockefeller do more harm than good in his aproach to governing New York State during multiple traditional and creeping crises?

Ed Kresky, an investment banker, who served as an aide to William Ronan when he was Rockefeller’s chief of staff and was one of Governor Carey’s first appointments to “Big Mac”[21] explained the Rockefeller financing this way: “…we could not have gotten the increment that we referred to, or an enlarged and better public service, very rapidly through the alternative of convincing the public in referenda. I don’t think that we could have gotten all that we got, if we paid less of a price and waited for referendum approval…it would have taken another generation to achieve these goals. So, in balance, I really don’t think there was much of an alternative” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1981, p. 221). We don’t have a ‘triple A’ rating, but what we do have is the heritage of Nelson Rockefeller, an incredible set of facilities and services that were meant to meet genuine public needs and have done so in a remarkable fashion…I’ve seen all too many states in this country where nothing is being given and they have a ‘triple A’ rating. I’d rather have what Nelson Rockefeller left behind: the great State University and City University systems; the enlightened programs in mental health, community affairs, the arts, and so forth.”

Perhaps the most important example of Rockefeller’s legacy is SUNY: In 1960, SUNY was a system of 41,000 students in 46 colleges devoted mainly to teacher education, and agricultural and technical programs (Glazer, 1989, p. 6). When Rockefeller left office in December 1973, SUNY had become the largest public university system in the US with 250,000 students studying on 64 campuses (Smith, 2014, p. 355) and by 1975 SUNY had grown to 357,614 students (Glazer, 1989, p. 6). From 1962-1982, the State University Construction Fund built $2.6 billion in academic buildings funded by bonds sold through the HFA (Smith, 2014, p. 376).

Alton Marshall, Rockefeller’s executive secretary from 1965-1971 and “de-facto” governor when Rockefeller was campaigning for the US presidency (Hevesi, 2008) explained the situation in stark terms: “There was no way to get Urban Renewal bonds passed in this State…There probably would have been no way, because of the selfishness that did exist in those people who could send their kids away to college–who would refuse to recognize the desperate situation we were in the State of New York in the way of higher education” (referring to the voters rejection of Rockefeller’s request for authorization for a $500 million bond) (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1981, p. 224).

Another important consideration is that during the years of intensive building of SUNY, hospitals, and wastewater plants, interest rates were low (bond financing was running about 2 percent). Delaying construction just two years on many projects would have cost taxpayers millions more in interest payments.

The economist, Dick Netzer (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 220) observed, “… my overall conclusion remains that the innovations were worthwhile for all the defects. The legacy is a vast increment to the public facilities and services of New York State.”

Changes to New York State Governance

Even a leader of Rockefeller’s caliber began to recognize that the fiscal balance between the federal government and the states had swung in Washington’s favor. He, alone could not reverse New York’s deindustrialization, hollowing out of her cities, and ensure decent housing for all New Yorkers. New York’s government simply could no longer bear the costs of innovation it had incurred in the first decade of his governorship. The fiscal crises left New Yorkers badly shaken. But to what extent did the threat of bankruptcy, the “drop dead” attitude of Congress and the President, and the ignorance public officials and business leaders professed in the aftermath of the crises affect governance in the Empire State?

First. The complexity of financing in the Rockefeller era had the effect of strengthening the separation of powers and checks and balances in a constitution that provides for a strong executive.

The 1965 budget battles convinced Democrats (who were then briefly in control of both houses) to begin hiring staff schooled in fiscal policy. When in the next year, Republicans regained control of the Assembly and Senate, they recognized the Democratic leaders’ wisdom and began professionalizing their staff. By 1968, the Legislature was better prepared to do battle with Rockefeller. So, for example, with some assembly members recalcitrant about raising taxes during a legislative election year and the budget passage delayed and Rockefeller, anxious to get out on the presidential husting, told The New York Times (1968), “At this point, I’ll take anything the bastards will give me.” As long-time Albany watcher Alan Chartock observed in 1984, “…we have a very, very strong Legislature. We did not have a strong Legislature when Nelson Rockefeller was the Governor. We didn’t have a strong Legislature because it didn’t have sufficient resources to compete with the Governor. And I think it’s an incredible irony of Nelson Rockefeller that it was his strength which led to the situation today where we have a Legislature which is competitive with the Governor…He forced them to compete” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 71).

Second. Limits to Home Rule. Greater oversight of municipalities (and later, counties). The invention of the fiscal control board.

Did New York State’s ‘innovative financing’ during the Rockefeller years contribute to NYC’s 1975 fiscal crisis? Probably not. NYC’s financial crisis can be attributed to the crushing weight of short-term debt the City’s revenues could not cover, in turn caused by the “New Federalism” policy changes enacted by the Nixon administration (reduction in funding for social programs for which NYC’s large indigent population depended) (Phillips-Fein, 2017; Temporary Commission on New YOrk Cty Finances, 1976). Municipal borrowing limits had always been based on the previous year’s revenues, but Mayor Wagner asked, and Rockefeller supported, a change so that the City could borrow based on projected revenues for the following year (and the Legislature agreed) (Ravitch, 2014, p. 81). Inadequate State oversight of NYC borrowing on bond markets to cover operating expenses continued under subsequent mayors (Lindsay and Beame). Time and again, the NYS Legislature acceded to the lobbying of NYC politicians for exemptions for diverse types of borrowing (short- or long-term depending on the useful life). Continual amending of New York’s Local Finance Law “eased the rules for issuing and rolling over short-term notes” McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981, p. 4).

The Legislature’s culpability extended to State entities as well. Richard Ravitch (2018, pp. 53 & 83), whom Carey named to chair UDC, explained the consequence of the Legislature’s refusal to cover Carey’s first request to appropriate $178 million to cover UDC’s short-term debts when the Nixon administration had cut funding for UDC projects. “It was clear to Carey, Goldmark (Carey’s budget director), and me that the state’s decision earlier in the year not to pay the debt of the Urban Development Corporation when it came due had had the unintended consequence of shaking the financial community’s confidence in the state’s ultimate willingness to pay the debts of other ‘creatures’ of the state, including public authorities and local government like New York City.”

The New York Times Editorial Board (1975) also warned that the State’s failure to bail out UDC could have dire repercussions in the financial community if bankers thought the State was unwilling to honor the moral obligation financing that had been the norm during the Rockefeller administration. As Greenhouse (1975), reporting on the deliberations of the Moreland Commission on the UDC observed, “What the agency’s failure showed was the scope of the burden the state had assumed. The program that was to have cost nothing was turning out to cost an enormous amount, and investors suddenly began asking questions about the full-faith-and-credit debt of the state itself.”

Various public officials who worked in state government during the 1960s-1980s did not accept the notion that NYC’s near default could be traced to the State’s innovative financing. Kresky, for example, said, “…if you think there was innovative financing by Rockefeller, you should research went on in the City of New York! I mean, they were geniuses at it” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 204). The economist Dick Netzer, however, offered a more nuanced view, suggesting that “Because the State government was doing highly unorthodox financing, it could not hold the City of New York to rigorous, conservative financing practices” …but “when the City government followed the routes pioneered by the State, it went much further, and it was far more imprudent. For example, the State invented bond anticipation (BAN), but it was the City (with legislative authorization) that carried the device to the extreme…by far the most irresponsible of the State-invented moral obligation bond was for the City Education Construction Fund, which was little better than a Ponzi scheme” (quoted in Benjamin and Hurd, 1984, p. 220).

The New York State Financial Control Board was created in 1975 to oversee NYC’s finances. In turn this model has been used to oversee NYC and served as the model for other struggling municipalities and counties (Buffalo, Troy, Yonkers, Erie County, Nassau County) – a permanent institutional innovation implemented as a result of the 1975 fiscal crisis.

NYC’s fiscal crisis also forced the issue of home rule into the forefront and the Legislature had to become more responsible in saying “no.” While NYC thought it could go alone, the fiscal crisis demonstrated that it needed the State. If NYC could not go it alone, how could Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Yonkers, let alone New York’s many small cities? Mayor Koch restored fiscal health to NYC by working cooperatively with State officials, in a strategy polar opposite from his predecessors Mayor Abraham Beame and Mayor John Lindsay. Observers also realized the power struggles between Lindsay and Rockefeller were not beneficial to either Albany or New York City. Rockefeller emphatically explained on many occasions that NYC could not go it alone no matter what the mayor said or how many schemes he promoted for more self-governance. Home rule was bestowed by the State and the State had to be the decider in grants-in-aid to local governments because only the State was in the position to understand the needs of all localities. After the 1975 crisis, no one took seriously any talk of NYC having more independence from Albany. Policymakers emerged with a better sense of the interrelated fiscal relationships between State and local government (New York State Division of the Budget, 1981).

Third. Moral obligation bonds are here to stay.

Prior to 1975, the NYS Division of the Budget (DOB) virtually ignored public authorities (McClelland & Magdoviz, 1981, p. 254). Under the Rockefeller administration PA indebtedness increased and was to change the way New York State financed growth. In the 1960 PAs accounted for 45 percent of state debt, but by 1970 they accounted for 61 percent (Rubenstein, 1992). Today, over 97 percent of all State-funded debt outstanding has been issued by public authorities without voter approval (OSC, 2024).

Rockefeller “celebrated moral obligation bonding as ‘the greatest system ever invented’” (Smith, 2014, p. 376). Supporters of moral obligation bonding consider it to be the price to be paid for delivering services to the public without sudden and large tax increases. And, of course, no NYS public authority has ever defaulted on their moral obligation bonds although the State spectacularly expended millions of dollars bailing out the UDC in the early months of 1975, while fixing UDC’s financial structure and redirecting the authority’s focus from housing for low- and moderate-income New Yorkers to economic development (along with a new DBA “Empire State Development Corporation”). And today? Bankers line up to underwrite moral obligation bonds and institutional and private investors like to buy them.

New York State Comptroller Arthur Levitt (the only statewide office held by a Democrat during the Rockefeller years) was the major voice opposing moral obligation bonds. NYS’s Comptrollers have continued to oppose what they call “backdoor financing,” because the debt issued by public authorities skirts the constitutional requirement to ask the voters for permission before indebting the State for future generations (see, for example, Bopst, 2016 and OSC, 2017).[23] No one paid much attention to Levitt or subsequent Comptrollers.[22] But Comptrollers follow debt closely and post information to the OSC’s website, which is important information for the public and policymakers.

Fourth. The public accepts public authorities, but wants oversight of some of the State’s public authorities.

While the Office of the State Comptroller continues to closely watch (and warn about) public authorities, there also have been several attempts at oversight since the 1975 NYC fiscal crisis. Box 3 lists various attempts to monitor public authorities, especially with respect to accountability, minority/women representation on their boards, and transparency, none of these reforms has been aimed at fundamentally reshaping the way in which PAs finance projects.

Box 3 NYS Oversight of Public Authorities

| -Temporary State Commission on the Powers of Local Government (1973) -Moreland Commission (1976) “Restoring Credit and Confidence: A Reform Program for New York State and its Public Authorities” -Public Authorities Control Board (1976) The PACB’s mandate is to review bond financing or construction commitments from 11 statewide PAs before entering into agreements. For example, the PACB had immediate oversight of the troubled UDC, with the authority to approve any project before the UDC could commit any funds to the project (Fried, 1979) -The Authorities Budget Office (ABO) (2005) was created by the Public Authorities Accountability Act of 2005 (signed by Governor George Pataki). -The ABO was restructured in 2009 under the Public Authorities Reform Act. The ABO is an independent watchdog, financed through fees levied on public authorities. -The OSC conducts audits to assess the financial health and management practices of PAs. -Standing Committees in the Assembly and the Senate exercising oversight of PAs. |

Henderson (2012, p. 217), in his review of New York’s public authorities, opines “Generally, they (PAs) are well regarded by the interested public who may see them as flexible, business-like and less immersed in politics” than other parts of state government. “Authorities will continue to play an important role in conflict resolution in New York State.”

There are now 591 public authorities operating in New York State (New York State Authorities Budget Office, 2023). The Office of the State Comptroller (2023) reported at the end of State Fiscal Year 2022-23:

- $1.8 billion of constitutionally authorized, voter-approved general obligation debt

- $55.9 billion of state-supported debt (nearly 97 percent of this state-supported debt is issued by PAs).

Fifth. The State University of New York as a decentralized system independent of the State Board of Regents with ability to finance capital projects through public authorities.

As Oscar Lanford, former president of SUNY Fredonia and General Manager of the State University Construction Fund (1971-1974) noted “the Rockefeller administration faced the need to accomplish in a few years what most other states had required a century to accomplish” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, pp. 79-80). The rapid growth in SUNY under Rockefeller was made possible by a combination of the SUNY Construction Fund and financing provided by the New York State Housing Finance Agency (HFA) had “become the envy of many other states.” And because much of SUNY’s infrastructure was built during a period of lower borrowing costs and the land and building value has appreciated, SUNY’s land and infrastructure had already appreciated substantially by the mid-1980s. Many SUNY campuses now occupy land in areas of the State with very high property values.

Importantly, Rockefeller ensured that SUNY would have a great deal of independence from state agencies and be able to make the decisions it needed to become a first-rate higher public education system. The independence of the nation’s largest public higher education system continues today (although this independence has recently been tested in light of NYS’s fiscal woes and the higher education enrollment cliff).

Rockefeller, as a devotee of the federal system, attempted to replicate in SUNY the features he identified as the mainspring of a working (rather than administrative) federal system: cooperation and competition. He established a public university system in which the system would encourage cooperation, but also expected the campuses to compete with each other, and in so doing, would become centers of innovation (just as States competing with one another and with the federal government, stimulates innovation).

Sixth. New York became more assertive in its demands that the federal government return more of New York’s tax dollars. The hollowing out of property tax bases in New York’s cities by white flight to the suburbs and outmigration from NYS, the shuttering of manufacturing plants, and the Legislature’s propensity for giving property tax exemptions together established New York’s need for more and more federal monies. Rockefeller began what is now a continuing tug and pull between New York and the federal government with respect to fiscal transfers (see Rockefeller 1968, 1971 and U.S. Congress, House, 1974). New York Senator Patrick Moynihan took up the torch questioning 1) federal formulas weighted to transfer more funds to impoverished and/or underdeveloped regions, ignoring the worsening problems of deindustrialized New York and 2) the federal government’s refusal to shoulder the full financial burden of social welfare programs, especially AFDC (TANF since the Clinton administration) and Medicaid.

Seventh. Being first is a gamble.

Some of Rockefeller’s legislative initiatives were later adopted practically in toto by Congress and his programs were so ahead of their time that no federal funding existed. (The consequence was that when the federal government “caught on,” New York paid the price for innovation in not qualifying for federal funds. The history of the UDC’s formation and insolvency is a good illustration of the problem of being first–the policy entrepreneur being overly dependent on federal initiatives. Rockefeller established the UDC in 1968 in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. as a multipurpose agency tasked with industrial development, housing, and economic development. In 1968, Congress enacted Section 236 of the Housing Act, authorizing HUD to provide interest-rate subsidies to lenders that limited developers’ profits and the UDC took full advantage of this subsidy. The UDC’s housing construction was intended to be financed partially by bonds issued for industrial development, but three months after UDC’s creation, the Congress passed a tax law that vastly diminished the ability to issue industrial development bonds (Edward Logue, quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 208-209). (The Treasury Secretary ruled that 90% of the bond revenue had to be used for housing and only 10% could be used for other projects.) This left the “largest state government agency of its kind in the nation” primarily dependent on projected receipts from housing rents rather than other sources of income (Lachman & Polner, 2010, p. 84).

The Moreland Commission that Governor Carey set up in 1976 to investigate UDC’s implosion found that it had become overly dependent on HUD’s program and had never made provisions for the possibility of its ending. At the end of 1974 the UDC had more than $1 billion in outstanding moral obligation bonds, many half-finished projects, and no money from either rents or HUD to complete them (Lachman & Polner, 2010, p. 85).

Eighth. New Yorkers like to be first, but sometimes this is out of necessity

Arguably, New York was an innovator between 1959-1974. (See Box 2.1, above.) New York’s willingness under Rockefeller to tackle water pollution, consumer protections, parks, labor rights (minimum wage), support for the arts, low-income and middle-income housing, rubber paying for rail –served a “laboratory of democracy” function for the country. The HFA, for example, had by 1982 been replicated in over 40 states (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 85). New Yorkers like to be ahead of the game, to be trail blazers, but as argued above, being first does not always “pay” in a federal system. This is a lesson that continues to inform debates between Democrats and Republicans in the Empire State. At the same time, sometimes New York must be first. The history of support for environmental legislation–in many respects the consequences of NYS’s geography–is a noteworthy example of the imperative of being first (see Buonanno, Floss, and Rabb, 2026).

Conclusion

The term “Rockefeller Republican” never applied beyond the Northeast, Midwest, and the West Coast states, but it defined an era in which a group of Republicans governing in increasingly Democratic states found middle ground by adopting a Hamiltonian view of governance. In effect, they were America’s 20th century Whigs. New York governors have faced down recessions and depressions and tackled creeping crises from unsafe conditions in the workplace and in housing (Al Smith), harnessed the power of government to mitigate the effects of the Great Depression (its epicenter and first impacts were in NYC – FDR and Herbert Henry Lehman), modernizing transportation and electricity generation (Thomas Dewey), clean water, expansion and funding for CUNY and SUNY in order to absorb the millions of baby boomers who would be graduating from high school (Nelson Rockefeller/Malcom Wilson/Hugh Carey), the 1971-1975 fiscal crises in NYS and NYC (Hugh Carey), 9/11 (George Pataki), the Great Recession (Eliot Spitzer and David Paterson), and the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change (Andrew Cuomo/Kathy Hocul). If one seeks examples of “laboratories of democracy,” New York represents a good case study. The ways in which Empire State governors have confronted crises continues to be instructive for not only other states, but in many cases New York’s solutions have been adopted in the nation’s capital. Rockefeller’s accomplishments and the legacy he left New York State makes him the the most influential governor since DeWitt Clinton, the governor who, against all odds, built the Erie Canal and in so doing transformed New York into the Empire State.

References

Barrett, M. E. (2022). Defining Rockefeller Republicanism: Promise and peril at the edge of the liberal consensus, 1958–1975. Journal of Policy History, 34(3), 336-370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030622000100

Benjamin, G., & Hurd, T. N. (Eds.). (1984). Rockefeller in Retrospect: The Governor’s New York Legacy. Rockefeller Institute of Government.

Bopst, C. (2016). The gift that keeps on giving: New York’s approach to gifts and loans of public money and credit. In P. J. Galie, C. Bopst, & G. Benjamin (Eds.), New York’s Broken Constitution: The Governance Crisis and the Path to Renewed Greatness (pp. 219-242). State University of New York Press.

Buonanno, L. A., Floss, F. G., & Rabb, G. (2026). New York’s climate change policy. In L. A. Buonanno, L. K. Parshall, F. G. Floss, & B. W. Brown (Eds.), Governing New York State through crises. SUNY Press.

Colman, W. G. (1974). The changing role of the states in the federal system. Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, 31(3), 73-84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1173210

Committee on Higher Education/Heald Commission. (1960). Meeting the increasing demand for higher education in New York State: A report of the Governor and the Board of Regents.

Connery, R. H., & Benjamin, G. (1979). Rockefeller of New York: Executive power in the statehouse. Cornell University Press

DASNY. (nd). History: Driving New York’s economy since 1944. https://www.dasny.org/about-us/history

Glazer, J. (1989). Nelson Rockefeller and the Politics of Higher Education in New York State. T. N. A. R. I. o. Government. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED319271.pdf

Greenhouse, L. (1975, November 9). Lessons to be learned from U.D.C.’s collapse. The New York Times. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1975/11/09/issue.html

Henderson, K. (2012). Other Governments: The Public Authorities. In R. F. Pecorella & J. M. Stonecash (Eds.), Governing New York State (Sixth ed., pp. 203-218). SUNY Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/buffalostate/detail.action?docID=3408680

Hevesi, D. (2008, January 26). Alton G. Marshall, 86, Nelson Rockefeller’s Top Aide, Is Dead. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/26/nyregion/26marshall.html

Lachman, S. P., & Polner, R. (2010). The man who saved New York: Hugh Carey and the Great Fiscal Crisis of 1975. SUNY Press.

McClelland, P. D., & Magdovitz, A. L. (1981). Crisis in the making: The political economy of New York State since 1945. Cambride University Press.

Narvaez, A. (1973, December 12). 2-year study is projects to define critical choices. The New York Times. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1973/12/12/91051116.pdf

New York State Authorities Budget Office. (2023). Public Authority Data: Directory of Public Authorities. https://www.abo.ny.gov/publicauthoritydata/PublicAuthorityDataDirectoryofAuthorities.html

New York State Division of the Budget. (1981). The executive budget in New York State: A half-century perspective. New York State Division of the Budget.

New York Times Editorial Board. (1975, February 27). A ‘Moral Obligation’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/02/27/archives/a-moral-obligation.html

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (2017). Debt impact study: An analysis of New York State’s debt burden.

https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/special-topics/pdf/debt-impact-2017.pdf

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (2023). 2023 financial condition report: For Fiscal Year ended March 31, 2023. https://www.osc.ny.gov/reports/finance/2023-fcr/debt

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (2024). Public Authorities.

https://www.osc.ny.gov/public-authorities

Phillips-Fein, K. (2017). Fear city: New York’s fiscal crisis and the rise of austerity policits. Henry Holt and Co.

Ravitch, R. (2014). So much to do: A full life of business, politics, and confronting fiscal crises. Public Affairs.

Representatives, U. S. H. o. (1974). Analysis of the philosophy and public record of Nelson A. Rockefeller, nominee for Vice President of the United States: Committe on the Judiciary, Ninety-third Congress, second session.

Rockefeller, N. A. (1962). The future of federalism (The Godkin Lectures). Atheneum.

Rockefeller, N. A. (1971). A Governor’s viewpoint on fiscal federalism. National Tax Journal, 24(3), 327-330. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41792259

Rubenstein, E. (1992). Cranking the debt machine: The politicization of public authorities is driving New York State futher into debt and threatens another fiscal crisis. City Journal, Winter. https://www.city-journal.org/article/cranking-the-debt-machine

Smith, R. N. (2014). On his own terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller. Random House.

State University Construction Fund. (nd). About the SUCF. https://sucf.suny.edu/about/the-fund

Temporary Commission on New York City Finances. (1977). Public assistance programs in New York City: Twelfth Interim Report.

Time Magazine. (1973, December 31). New York: No. 2 makes good. Time.

United States Senate. (1957, October 4). Sputnik spurs passage of the National Defense Education Act. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Sputnik_Spurs_Passage_of_National_Defense_Education_Act.htm

United States. Congress. House. Committee on the Judiciary. (1974). Analysis of the Philosophy and Public Record of Nelson A. Rockefeller, Nominee for Vice President of United States, 93d Congress, 2d Session, Oct. 1974.

Vitello, P. (2013, January 30). Edward M. Kresky, who calmed fiscal panic, Dies at 88. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/31/nyregion/edward-m-kresky-88-calmed-fiscal-panic.html

[1] About three-quarters of the decline was accounted for by apparel, food, leather, and printing (McClelland & Magdovitz, 1981, p. 33).

[2] The number of births in New York State in 1940 was 199,000; 302,000 in 1950; and 363,000 in 1959. The Heald Report estimated 398,000 births for 1965. The number of high school graduates was 140,000 in 1959, with estimates of 214,000 by 1965 (Heald Commission Report, 1960, p. 51). Compare these numbers to 2022, when there were 207,590 births and 175, 886 students graduated from high school (New York State Department of Education, State Data. https://data.nysed.gov/gradrate.php?year=2022&state=yes).

[3] Looking back on SUNY pre-Nelson Rockefeller, it is astounding when one realizes that only one SUNY campus conferred a liberal arts baccalaureate, Harpur College, which became part of the new Binghamton University in the SUNY system.

[4] Rockefeller remained supportive of the Vietnam War long after New Yorkers had begun to think it was time for the US to withdraw its troops. Rockefeller had a lot of good ideas, but his promotion of bomb shelters to survive nuclear attack was not one of them. For more on this fiasco, see Smith (2014). With respect to the NDEA, “it established the legitimacy of federal funding of higher education and made substantial funds available for low-cost student loans United States Senate. (1957, October 4). Sputnik spurs passage of the National Defense Education Act. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Sputnik_Spurs_Passage_of_National_Defense_Education_Act.htm. The NDEA is an exemplar of policy entrepreneurship. Senate sponsors had faced years of disappointment in attempting to pass a bill authorizing federal assistance for higher education because the House of Representatives voted down the legislation. Sputnik accomplished what the lobbyists could not.

[5]The LBJ Library. (1965). LBJ and Nelson Rockefeller, 11/9/65: Power Outage. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=italegDRFlE recording of LBJ and Rockefeller discussing the 1965 Northeast blackout.

[6] Prior to the 1962 Baker v. Carr one-man/one-vote SCOTUS ruling and subsequent reapportionment cases Republicans had malapportioned the legislature, especially the Senate, to favor upstate and rural areas. Between 1950 and 1973, the Legislature was reapportioned four times. See Connery, R. H., & Benjamin, G. (1979). Rockefeller of New York: Executive power in the statehouse. Cornell University Press (p. 78.)

[7] Rockefeller won his 1958 election by a plurality of 573,034 votes, 1962 by 529,169 votes, and 1970 by 730,006 votes Benjamin, G., & Hurd, T. N. (Eds.). (1984). Rockefeller in Retrospect: The Governor’s New York Legacy. Rockefeller Institute of Government. (p. 51). He is the only individual to have been elected governor of NYS four times for four-year terms.

[8] FDR’s Vice-President Henry Wallace observed, “Nelson Rockefeller’s definition of a ‘coordinator’ is a man who can keep all the balls in the air without losing his own” Smith, R. N. (2014). On his own terms: A Life of Nelson Rockefeller. Random House. (p. 143).

[9] Rockefeller wasn’t the only governor spending. During this time period, State spending was on an upward trajectory throughout the U.S.

[10] In a speech to the Empire Chamber of Commerce, Rockefeller said, “Personally, I feel that to the maximum degree possible, we should finance out of current income in government, because we make the taxpayers pay up to and over fifty percent more for their roads, their hospitals, and their mental institutions, by financing out of bond sales.” Quoted in Connery & Benjamin Connery, R. H., & Benjamin, G. (1979). Rockefeller of New York: Executive power in the statehouse. Cornell University Press (1979, pp. 222-3).

[11] Of course, whether high-benefit states were welfare magnets was a highly-contested subject during the 1980s through 1996 when President Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, which replaced AFDC with TANF. The evidence at the time seemed to suggest that while high-benefit states were not attracting the poor, generous benefits were retaining them (Schram & Krueger, 1994). Another phenomenon was the “reverse freedom riders,” a heavily publicized phenomenon in the 1960s, one that is echoed in contemporary one-way bus tickets provided by Florida and Texas for irregular migrants to Chicago, Detroit, New York.

[12] See Barrett (2022, 2024) for another interpretation. She argues that over time Rockefeller became more conservative as he attempted to persuade Republicans, especially in the South and West, of his fitness for national office.

[13] Full faith and credit of the state. McClelland and Magdovitz (1981, p. 281) explain that “this wording is designed to signal to prospective creditors that these obligations would have first claim, or first lien against tax revenues.”

[14] Rockefeller’s most persistent critic, Arthur Levitt, NY’s Comptroller and only Democrat elected to statewide office during the Rockefeller years recognized Rockefeller’s innovative governing, commenting, “He would have made a great president.”

[15] Article X, Section 5. “Neither the state nor any political subdivision thereof shall at any time be liable for the payment of any obligations issued by such a public corporation heretofore or hereafter created, nor many the legislature accept, authorize acceptance of or impose such liability upon the state or any political subdivision thereof…”

[16]John Mitchell explained the genesis of moral obligation bonds in a 1984 interview with the Bond Buyer, quoted here by Rubenstein (1992). [When] Nelson Rockefeller was elected the Governor of New York in 1958, the voters turned down all of the propositions that had to be voted [on] under the state constitution—for housing, mental health, etc. His director of housing was telling me about the state’s problems. To keep the interest cost down and have a security that would be marketable, I transferred over to the Housing Finance Agency (HFA) a concept [of moral obligation bonds] that had been used temporarily in connection with school districts. I just took that and adapted it to the Housing Finance Agency and structured the mechanics of it. It went very, very well and the bonds were marketable, the interest rates were more than reasonable, and, of course, we took it from there. Within a few years HFA debt exceeded that of the state itself. By 1973 HFA had gone far beyond its original mandate of financing housing, becoming, in the words of Annmarie Walsh, author of The Public’s Business, “an investment banker for a varied mix of public and private agencies, financing not only housing but hospitals, nursing homes, mental health facilities, youth and day-care centers, senior citizen centers, and the state university.”

[17] The Treasury Secretary ruled that 90% of the bond revenue had to be used for housing and only 10% could be used for other projects.

[18] DASNY’s first dormitory was built in 1948 at Buffalo State Teachers’ College. In 1954, DASNY and SUNY signed a lease agreement that SUNY would operate DASNY-built dormitories (DASNY, nd).

[19] New York and five other states have had a negative balance of payments up until as recently as 2019, when NYS ranked 49th. No state had a negative balance in 2020 due to the federal government providing mass amounts of COVID-19 pandemic aid. Yet even with this aid, in 2020 NYS received $1.59 for every $1 sent to DC, compared to a national average return of $1.92 DiNapoli, T. P. (2022). New York State Comptroller: Annual Financial Conditions Report. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/finance/pdf/2022-financial-condition-report.pdf.

[20] The “de jure” leader was Emmanuel Celler, who was “dean of the House of Representatives” (longest continuously serving member) until his loss to Elizabeth Holtzman in the 1972 Democratic primary. Celler holds the record of the longest serving member of Congress from NYS.

[21] Kretsky secured sales of its bonds by guaranteeing that bondholders would be paid first from NYC sales tax revenues – see Vitello, P. (2013, January 30). Edward M. Kresky, who calmed fiscal panic, Dies at 88. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/31/nyregion/edward-m-kresky-88-calmed-fiscal-panic.html.

[22] Levitt bought $25 million worth of MAC bonds for the NYS Pension Fund after being asked to do so by Governor Carey, along with Majority Leader Warren Anderson, Speaker Steingut, and about 20 bankers. Levitt sold them a year and a half later at a large profit (story related by Edward Kresky in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 200).

[23]McClelland & Magdovitz (1981, p. 234) write, “As a constitutional end run, the moral obligation bond is a masterpiece.”

Suggested Citation: Buonanno, L. (2024). Nelson A. Rockefeller and crisis governance. Governing New York State Through Crises Project (June 26). https://governingnewyork.com/essays/nelson-a-rockefeller-and-crisis-governance/

About the author

Laurie Buonanno, Ph.D., is a professor of political science and public administration at SUNY Buffalo State University.