Laurie Buonanno and Lisa Parshall

July 29, 2024

Introduction

As the executive of a large state and the state’s primary interface in the intergovernmental system, New York’s governors have been critical players in national politics (Beyle, 1999, p. 203 & 223)(Beyle 1999, 203, 223). George Weeks (1982) included three New York governors in his top ten list of “Statehouse Hall of Fame,” based primarily on “those governors who made a difference not only in their states but also on behalf of states and the federal system” in the twentieth century.[1] A biographer of both Thomas Dewey and Nelson Rockefeller, Richard Norton Smith observed, “New Yorkers like their governors strong, stylish, and, like themselves, a little bigger than life,” observed Richard Norton Smith (2008, p. 63), an interpretation corroborated by Willam Ronan, Governor Rockefeller’s long-time secretary: “New York is a big, dynamic, high-powered state and it wants a big, dynamic, high-powered man for its governor” (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 418). Morgan (1981, p. 142) observed that because New York combines the “political cultures of the Midwest and Europe,” an effective NYS governor is seen as “presidential timber” and the NYS governorship has long been an “audition” for the presidency (Smith, 2008, p. 64).

This essay begins with an examination of the New York’s governor’s formal and informal powers. We then examine the specific powers New York’s governors can employ to manage crises.

A Strong Executive

How does New York State’s executive compare to other states? There is some disagreement among scholars. Smith and Greenblatt (2022, p. 239), for example, rank New York thirteenth place (along with Wyoming) in the index of institutional powers. New York receives full marks for tenure potential (four-year term with no restraint on reelection) and veto power.[2] New York is in the middle range for separately elected executive branch officials (as some statewide offices are independently elected)[3] and appointment power (as shared or requiring approval). Where New York scores low is on gubernatorial budget authority (shared with the legislative branch) and party control (measured prior to the Democratic trifecta). Yet, factoring in New York’s size and gross state product, along with the extensive powers granted governors over the state’s economic activity and taxing power, “the governor of New York may be the second most powerful chief elected executive in the nation, behind only the president” (Ward, 2006, p. 59). Another student of New York State government and politics, Robert Connery observed, “The Governor proposes and the Legislature disposes…” adding “no governor in any other state has the power and authority that the Governor of New York has” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 281). In skilled hands, this individual can very aptly be said to be an “imperial” governor.[4]

* * *

New York has a history of strong gubernatorial powers dating back to the colonial period when New York opted for a strong executive rather than the strong legislature other states were writing into their first constitutions (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 23).[5] This choice reflected New York’s unique circumstance because as historian Edward Countryman (2001, p. 234) explains, “No state experienced the Revolutionary War with greater ferocity or over a longer period than New York.” New Yorkers wrote their first state constitution in 1777 under British occupation (New York City was the headquarters for the British until they evacuated on November 25, 1783) where the advantages of a strong executive seemed obvious (Roper, 1974, p. 20). Indeed, John Jay (the principal drafter of New York’s first constitution) was determined to balance order (republicanism) and liberty (liberalism), in a conscious attempt to find middle ground between Pennsylvania’s emphasis on liberty and Maryland’s elitist approach.[6]

Governors have formal and informal powers. Formal powers are derived from the NYS Constitution and subsequent court interpretations. Informal powers tend to be those that are inherent to the executive, but also those derived from characteristics unique to the Empire State. (See Table 1.1 for a summary.) The next section undertakes an analysis of formal and informal powers followed by a study of the governor’s powers to manage crises.

Table 1 New York Governors’ Formal & Informal Powers

| Formal Powers Large executive bureaucracyAnnual and special messagesShapes executive budgetVeto of legislationChapter amendmentsCan call the legislature into special sessionMessages of NecessityIndefinite eligibility to run for re-electionLine item veto Informal Powers Most visible public official in New York StateNational media headquarters in NYCAppearances at highly public events promotes visibility with the publicLeader of their partyControls substantial patronageControls information through the executive bureaucracySupport staff to develop source materialPublic expectations that the governor is the state’s leaderCall for task forces, especially the Moreland Commissions Crisis Management Messages of NecessityEmergency Powers |

Formal Powers

Elections and Tenure

New York deviated from the national trend (limited executive authority and term limits) in the post-Revolutionary period, establishing three-year terms for the governor (rejecting the one- and two-year terms in most states), without limitations on re-election in the 1777 Constitution.[7] Bucking another trend, the governor was directly elected rather than being selected by, and thereby being directly accountable for his job, to the electorate rather than to the state legislature.

A 1937 constitutional amendment extended the term for governor to four years, putting the “parameters of the modern New York governorship…in place” (Benjamin, 1989, p. 146), and importantly set the gubernatorial election during general (congressional elections) rather than during presidential election years. The latter point is important because prior to this constitutional revision, New York’s governors had to decide between running for president or attempting re-election.[8] A further constitutional change came about when New Yorkers voted in November 1953 to end the practice of separately electing the governor and lieutenant governor.[9]

Veto Power

New York’s 1777 Constitution provided for the governor’s membership in a Council of Revision (composed of the governor, the chancellor, and the supreme court justices) that could veto proposed laws. The 1821 Constitution enhanced the governor’s power by abolishing the Council of Revision and placing the veto solely in the governor’s hands. Revisions in 1846 added more statewide elected officers but left gubernatorial powers otherwise unchanged.

From 1872 until 1976, the legislature never attempted to override the governor’s veto (Benjamin, 2020). By the 1975 fiscal crisis the relationship between the legislature and governor had changed as the former gained more budgetary expertise so that when in 1976 Governor Carey’s sought to preserve his budgetary decrease of funding for NYC’s public schools, the legislature overrode Carey’s veto of legislation (Benjamin, 2020). Nevertheless, there have been just six successful legislative overrides of governors’ vetoes, all over financial issues (Benjamin, 2020). Since 2020, however, the legislative threat to override the governor’s veto has become more significant due to Democrats controlling both houses by veto-proof majorities.[10]

Chapter Amendments

A consequence of the Governor’s veto power is the ability to shape a bill not just during its drafting, but also after it has been passed. The Legislature passes the bulk of legislation days before recessing in June. Governors then must begin reviewing the legislation and have long complained that this compressed time frame undermines their ability to study the ramifications of legislation. Studying all the legislation that has been introduced in any one session and starting negotiations early (January) is a waste of time because thousands of bills can be introduced, however, most of the legislation–for a number of reasons–will not generate sufficient support to be passed. But even those bills that are passed–805 in 2024, 823 in 2023, 1007 in 2022– require time for the Governor’s staff to digest (Ashford & Fahy, 2024; Reinvent Albany, 2023). Therefore, the Governor and her staff are faced with the daunting task of signing hundreds of bills passed by the constitutional requirement of ten days is not practical.[11] Instead, through an informal agreement between the Legislature and the Governor, the latter “calls up” batches of bills when she is ready to either sign, veto, or modify them through “chapter amendments.” Negotiations on contentious bills take place in December between the “three men in the room,” but also with the Assembly and Senate sponsors of the bill. Between June when the bill was passed and December when the Governor makes her decision, she will have had time to consult with experts (when needed) and hear from the bill’s supporters and opponents. If the Governor wishes to sign the bill, but wants modification, she can negotiate chapter amendments with legislative leaders, which are laid out in the approval letter accompanying the signed law. The chapter amendment is then passed by the Legislature in the next session. Sometimes the chapter amendment is a technical improvement–perhaps a provision in the bill that is unworkable that the staff or legal counsel or an interest group caught during the consultation period. Other times–and here is where the governor’s power is increased–she can use the ever-present threat of the veto to extract changes to the bill even if these amendments substantially alter elements of the bill. Watchdog groups complain that Andrew Cuomo “ramped up the process, turning chapter amendments into a powerful executive tool” (Bragg & Mellins, 2024). Governor Hocul has gone further than Cuomo–amending “roughly one out of every seven bills sent to her–twice as many” as had Andrew Cuomo (Bragg & Mellins, 2024).

Gubernatorial Appointments & Head of a Large Bureaucracy

The executive office–often referred by Albany insiders as “the second floor”–is comprised of a secretary to the governor (who manages policy development), a counsel to the governor (who manages the governor’s legislative program), a director of state operations (who manages the governor’s priorities in policy implementation), and the state budget director (who manages the executive budget), along with a bevy of support staff and assistants. There are 188,455 employees (full-time equivalents) in agencies under the governor’s control (Girardin, 2023).[12]Thus, New York’s governors have a large bureaucracy that can implement a variety of programs and engage in regulatory activities.

Under the 1777 Constitution of New York, the appointment power was vested in a Council of Appointment composed of the governor and four senators. Reflecting Martin Van Buren’s leadership in the forging of the strong, patronage-based political party (epitomized by the Albany Regency) and as a member of the 1820 constitutional convention, the 1821 Constitution abolished the Council of Appointment, placing appointment of state judges in the governor’s hands.[13] In the 1970s, the NYS Senate introduced an advice and consent rule that forced governors to negotiate on appointments with the state legislature and a 1977 constitutional amendment altered the process for judicial appointments (limiting the governor’s choice to a list prepared by a 12-person nominating committee). Nevertheless, the governor’s appointment powers have been relatively unchallenged. Naturally, the appointment of state judges continues to be a powerful patronage tool wielded by New York’s governors.[14]

The late 19th century-early 20th century Progressive Movement had an enormous influence in shaping the powers of New York’s governor. Progressives argued that more power needed to be transferred to the executive in both the federal and state governments for two main reasons: establishing a cadre of professionals in a merit-based civil service and tamping down the rampant corruption associated with legislative bodies. At the time many of the department heads were independently elected, submitted their budget requests to the legislature (rather than the governor) and often belonged to parties other than the governor’s.

Progressives dominated New York’s Constitutional Convention whose delegates wrote a constitution expanding gubernatorial powers. These innovations owed much to Robert Moses’ progressive vision of a strong executive as necessary for governing complex, industrialized societies. The political commentator Walter Lippman thought Moses’ plan to bring agencies out of legislative control and under the governor’s control was “one of the greatest achievements in modern American politics” (Caro, 1975, pp. 260-261).

While the voters rejected the 1915 constitution, subsequent referendums during Governor Smith’s administration incorporated constitutional amendments from the 1915 effort. So, for example, in 1925 a short ballot was reintroduced that expanded the executive appointment authority by reducing the number of statewide elected officials to four – governor, lieutenant governor, comptroller, and attorney general. Smith persuaded the legislature to approve and the voters to ratify the consolidation of 187 boards and commissions into 19 departments, with the head of each appointed by the governor and serving at his pleasure (Peirce, 1972, p. 21). Evers (2013, pp. iv-v) comments that “By the end of Smith’s tenure as governor New York State had undergone a wholesale change strengthening the state’s chief executive and reordering state government. Smith’s transformative efforts enabled future governors to hold subordinate executive branch employees accountable, check the power of the legislature in state administration, and established the governor as the state’s leading administrative, budgetary, and policy making official.”

Tasks Forces & Commissions

New York’s Progressives advocated for the governor to be empowered to create executive commissions and study panels (“task forces”) both to tackle problems and to root out corruption. The Moreland Act 1907 – the legislative basis for governors to appoint a Moreland Commission to investigate operations of a state agency is a creature of this era (Connery & Benjamin, 1979, p. 175). Some of the more famous Moreland Commissions have been Nelson Rockefeller’s Commission on the Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) Law, Hugh Carey’s Commission to Investigate Nursing Homes and a Commission to study the default of the Urban Development Corporation, and Andrew Cuomo’s call for a Commission to Investigate Public Corruption.[15]

The Executive Budget

In 1927, voters granted the governor budgeting authority or what today we call the “Executive Budget.”[16] Furthermore, the “no-Alteration” clause prohibits legislative changes to executive appropriation bills.[17] Court rulings have upheld the governor’s line-item veto (a power even the American president does not enjoy). While the legislature has attempted to claw back budgetary power, voters rejected a constitutional amendment referendum in 2005 that would have restored legislative budgeting (Zimmerman, 2008). In the 1980s, the courts ended executive impoundment authority and judicial decisions of the 1990s reaffirmed limited legislative authority to rewrite governor’s appropriation bills.[18]

Setting the Agenda

The governor is required to give an annual State of the State message which provides a platform for agenda-setting. State of the State Addresses thus have become a primary means through which governors communicate their policy agenda (Ward, 2006). The Governor’s address is a televised and live streamed event that is reported on by “Albany watchers.” Furthermore, prior to the State of the State and immediately after, the governor’s staff works to build up support with the public for the governor’s budgetary priorities both through the media and in the governor’s public appearances.

The governor also can set the agenda by recalling the legislature for a special session. Albany can be a long, tedious drive on the NYS Thruway for those upstaters without access to regular Amtrak service, many legislators have other jobs–two of many reasons the governor’s power to call a special session can be an unwelcome disruption for legislators.

Informal Powers

The political dynamics of New York have advantaged governors, arguably to the detriment of a democratically deliberative state legislative process. The idea of “three men in a room” – a phrase coined by writers at Newsday – has become shorthand for power wielded by the governor and the state assembly and senate leaders in negotiating budgets and legislation (Liebman 2015). New York’s governors have wielded the informal powers of their office to great effect and as the champions of various reforms. In his long tenure as governor, Al Smith pioneered workmen’s compensation, reform of mental health institutions, overhaul of the executive branch, and (along with his close and loyal aide Robert Moses) established the New York State Park system. Nelson Rockefeller bypassed penny-pinching upstate Republicans to take his case to the working- and middle-class voters for their support to build a first-class public higher education system. It was the tenacity and public cajoling of Mario Cuomo that pushed through state ethics reform in 1987 (Ward, 2006, pp. 67-68). Andrew Cuomo championed the green economy and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Kathy Hocul has made affordable housing the centerpiece of her governorship. In policy parlance, governors often serve as policy entrepreneurs, translating campaign agendas into public policy solutions, advocating for reform, or championing signature policies and programs as leaders of their state.[19]

Governors and Crisis

Despite the formal powers of the office, political scientists have occasionally lamented a lack of leadership, and ineffective use of the informal powers of the office (Benjamin & Benjamin, 2012; Ward, 2006). As with the federal executive, the power of New York’s governor expands in times of crisis commensurate with public demand and expectations. Indeed, the “power-enhancing qualities of crisis are well known to governors and their advisors, and at times leads them to cultivate [a crisis] atmosphere” in state politics (Benjamin, 1989, p. 146). Connery and Benjamin (1979, p. 154) explain “the governor at any time (can) be thrust to center stage by a crisis in state or local government” and crisis management “becomes one of the key tests” of the governor’s administration.

Indeed, governors often advocate for policy solutions by labeling the situation or possible problem a “crisis.” Nelson Rockefeller as a reformer echoes Wildavsky’s (1969, p. 3) observation that “Creativity consists of finding a problem about which something can and ought to be done” – which he famously and concisely summarized as – “no solution, no problem.” Governor Rockefeller, an archetypal policy entrepreneur, often spoke in the language of “crisis,” believing that only when the public recognized something as a crisis, would public opinion support his policy proposals. As his Lieutenant Governor Malcom Wilson explained, “Nelson always acted on the premise that it was best to try to discern a problem as it was emerging over the horizon and undertake to transform it into an opportunity, rather than to let the problem grow and grow until it blew up to such proportions as to make it difficult, if not impossible, to effect a satisfactory solution…the whole thrust of Nelson’s major programs during his fifteen years as Governor…(was) ‘transforming problems into opportunities’” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 22). Of course, there is risk to engineering crises or crisis-claiming insofar as successive crises, the inability to resolve them, or the perception of a failed response drags down public approval. To a significant degree, public approval of executive performance depends not just on the day-to-day administration of the state but is heavily impacted by the ability to respond to crises (Beyle, 1999, p. 191). In short, “…the governor is praised when things go well and blamed when they go wrong” (Benjamin & Benjamin, 2012, p. 121). Needless to say, scandals and political corruption have become career ending crises for several of New York’s recent governors.

Executive Tools in Managing Crises

Messages of Necessity

The Message of Necessity is provided for in Article III, Section 14 of New York’s Constitution. It provides an exception to the Constitution’s three-day (aging) rule for legislation. New York’s first three constitutions (1777, 1821, and 1846) did not provide an “aging provision,” but rather left the decision to the legislature (Galie, 2016, p. 138). With very little discussion or debate, message of necessity provisions were added to the New York State Constitution in 1894, allowing governors to bypass the constitutionally prescribed three-day curing (or aging) period for legislation. Furthermore, the governor was not required to justify a necessity message (an executive statement of rationale directing the legislature to take an immediate vote). Legislation so approved precludes legislative amendment and dictates final passage upon majority approval (N.Y. Const. Article III, §14).

Between 1894-1915, 502 laws passed under necessity messages (Galie, 2016, p. 142). Delegates to the 1915 constitutional convention proposed the elimination of the message of necessity on grounds that it was “subject to abuse and had little redeeming value” (Galie & Bopst, 2013), but the voters rejected the revised constitution. The constitutional revisions proposed by the 1938 Constitutional Convention included an amendment, passed unanimously by the delegates, that the governor would need to certify the facts for a message of necessity. This amendment was included in the constitutional changes approved by the voters (Galie, 2016). Despite this amendment, courts have ruled that governors are not required to lay out the reasons for a necessity message on the grounds that “circumstances necessitating the haste may make it impracticable to prepare a detailed and persuasive message” (quoted in Galie, 2016, p. 147) and it has been used to pass legislation over 400 times since 1938. Furthermore, unlike the situation in some other large states (California, Floridia, New Jersey, Ohio, and Virginia), New York’s Constitution does not provide for a legislative override of the message (Galie, 2016). Figure 1.1 charts the use of this mechanism in recent times, where indicates their usage has decreased over time especially in comparison to the Pataki Administration when he frequently resorted to messages to push his embattled budget through the Assembly and Senate (Reisman, 2023).

Nevertheless, the continued ability of New York’s governors to easily bypass the three-day legislative calendar rule continues to be criticized by a bevy of good-government reform groups and constitutional reform advocates as unmoored from its original purpose of expediency in true emergencies to a political tool of governors to circumvent regular legislative order and debate (Galie & Bopst, 2013). Undoubtedly, as many observers have pointed out, the way in which the courts have interpreted the necessity message has had the effect of increasing the governor’s power vis à vis the Legislature.

Figure 1 Annual Messages of Necessity (1995-2023)

Data Source: https://www.nypirg.org/pubs/202306/End-of-Session-Review-2023.pdf

The debates of the message of necessity reflect the tensions between the theoretical need for executive action on matters of pressing concern and the desire to check executive control. A 2005 report by the Brennan Center for Justice, found that the “Historical evidence indicates that the constitutional provision that created the message of necessity has never really functioned as intended” (Creelan & Moulton, 2005, p. 29). Rather than responding to real emergencies, opponents claim, governors and legislative leaders (particularly the “three men in a room”) have used the message as a means of bypassing debate and public feedback on legislation, especially during the crunch to pass on-time budgets.

The message of necessity faced renewed criticism during the administration of Andrew Cuomo, who while not using the message as much as previous governors, employed it to win passage of controversial legislation: Marriage EqualityAct (2011), the New York Secure Action and Firearms Enforcement Act (NY SAFE Act), the property tax cap, rent control, mandated teacher evaluations, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, and a new government employee pension tier. However, if one looks closely at the history of the Marriage Equality Act, one can see that legislators had many opportunities to become familiar with the Act. The legislation had been introduced in previous legislative sessions and had passed in the Assembly four times since 2007, before Governor Cuomo used a Message of Necessity in the Senate to call a vote in 2011. The CLCPA had a similar legislative history. The SAFE Act, however, is different. Cuomo introduced the SAFE Act in response to the horror and real concern by many New Yorkers over two mass shootings in December 2012: the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre in Newtown, CT and the Webster, NY arsonist’s targeting and shooting of first responders. Detractors of the Message pounced on “substantive and stylistic errors in the bill,” suggesting errors could have been avoided if there had been hearings held and testimony obtained (Galie, 2016, p. 144). Yet the legislation’s oversights – magazine size and whether police officers would be exempt – were easily remedied.

Emergency Powers

Under New York’s constitution, the legislature is entrusted with the authority to suspend the constitution and state laws in order to respond to emergencies.[20] The legislature, in turn, has empowered the governor to issue such emergency declarations and supporting directives (including the suspension or alternation of state laws and regulations) by executive order (Executive Law, Chapter 19, Article II-B Section 28; 29).[21] These declarations cannot last more than 180 days but may be extended for additional periods not to exceed six months. Governors also have the authority to request federal assistance when they determine that “disaster is of such severity and magnitude that effective response is beyond the capabilities of the state and the affected jurisdictions” (Executive Law, Section 28-4). Gubernatorial disaster orders can be rescinded by the governor or terminated by a concurrent resolution of the legislature.

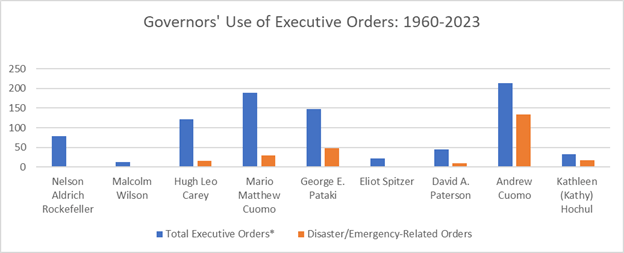

Figure 1.2 charts the governor’s use of executive orders from Rockefeller to Hochul (as of October 13, 2023), excluding extenders. Political observers have noted the increase in gubernatorial reliance on executive orders. The rate of emergency declarations (and related orders) has also risen, constituting some 62.4 percent of the executive orders issued by Andrew Cuomo and 51.5% of those issued thus far by Governor Hochul, compared to 32.7 percent and 15.9 percent by Governors Pataki and Mario Cuomo, respectively.

Figure 2 Governor’s Use of Executive Orders: 1960-2023

The increased use by New York’s governors of emergency orders might signal New York is facing more crises or it could be that recent governors have been taking advantage of this power. Watchdog groups argue that both Governors Cuomo and Hocul have abused their emergency order power to usurp legislative and comptroller oversight. In 2023, the Comptroller and his watchdog and legislative allies succeeded in passing legislation that would have required the executive agencies to post non-bid contracts to a website, but Hocul vetoed the legislation (Lombardo, 2024). The Legislature can rescind governors’ emergency orders (although they never do), but they do not have the power to affirm an emergency order the governor puts into place (Lombardo, 2024).

Conclusion

This essay has reviewed the major powers of New York’s governors, both constitutionally (formal) and informal powers. The executive is a crucial (if not the crucial) actor responsible for recognizing crises and marshaling the resources to resolve them.

Works Cited

Archie, A. (2022). Andrew Cuomo Files a Complaint Against Letitia James for her Sexual Harassment Report. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/14/1122894632/andrew-cuomo-letitia-james-new-york

Ashford, G., & Fahy, C. (2024, June 8). In final analysis: N.Y. legislative session is defined by its omissions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/08/nyregion/congestion-pricing-legislature-ny.html

Benjamin, G. (1989). The Governorship in an era of limits and change. In P. W. Colby & John K. White (Eds.), New York State today (pp. 143-156). SUNY Press.

Benjamin, G. (2020, December 20). New York and the veto–proof legislature. Gotham Gazette. https://www.gothamgazette.com/130-opinion/10014-new-york-veto-proof-legislature-governor-cuomo-override

Benjamin, G., & Benjamin, E. (2012). New York’s Governorship restored? In R. F. Pecorella & J. M. Stonecash (Eds.), Governing New York State (pp. 105-116). SUNY Press.

Benjamin, G., & Hurd, T. N. (Eds.). (1984). Rockefeller in Retrospect: The Governor’s New York Legacy. Rockefeller Institute of Government.

Beyle, T. L. (1999). The governors. In V. Gray, R. L. Hanson, & H. Jacob (Eds.), Politics and the American states (pp. 191-231). Congressional Quarterly.

Bragg, C., & Mellins, S. (2024). How the Governor upends bills Before signing them. New York Focus. https://nysfocus.com/2024/01/17/kathy-hochul-andrew-cuomo-chapter-amendments?oref=csny_firstreadtonight_nl

Caro, R. (1975). The power broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York. Vintage Books.

Confessore, N. (2010, September 23). Spitzer says Cuomo fights dirty. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/24/nyregion/24spitzer.html

Connery, R. H., & Benjamin, G. (1979). Rockefeller of New York: Executive power in the statehouse. Cornell University Press

Countryman, E. (2001). From revolution to statehood (1776-1825): Chapter 13 Never a more total revolution. In M. M. Klein (Ed.), The Empire State: A History of New York (pp. 229-240). Cornell University Press.

Creelan, J. M., & Moulton, L. M. (2005). The New York State legislative process: An evaluation and blueprint for reform. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/d/albanyreform_finalreport.pdf

Evers, J. T. (2013). Investigating New York: Governor Alfred E. Smith, The Moreland Act, and reshaping New York State Government (Publication Number ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 3561764) [Doctoral, University of Albany]. Albany.

Galie, P. J. (2016). “Mixed Messages”: The Governor’s Message of Necessity and the legislative process in New York. In P. J. Galie, C. Bopst, & G. Benjamin (Eds.), New York’s broken constitution: The Governance crisis and the path to renewed greatness (pp. 135-159). State University of New York Press.

Galie, P. J., & Bopst, C. (2013). “”It Ain’t necessarily so”: The Governor’s “Message Of Necessity” and the Legislative process In New York.” Albany Law Review 76(4), 2219-2299.

Girardin, K. (2023, March 9). Does NY have too many state workers? Empire Center. https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/does-ny-have-too-many-state-workers/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20employees%20in,equivalents%20as%20of%20October%202022.

HBO/MAX. (2023, November 3). Bill Maher Interview with Andrew Cuomo and Melissa De Rosa.

Kingdon, J. (2011). Agendas, alternatives and public policies (Updated 2nd ed.). Longman.

Lombardo, D. (2024, January 4). Reining in the Governor’s Emergency Powers In Capitol Pressroom.

Morgan, D. (1981). Review of Rockefeller of New York: Executive Power in the Statehouse. Journal of American Studies, 15(1), 142-143.

Peirce, N. R. (1972). The Megastates of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Ten Great States. W.W. Norton.

Pocock, J. G. A. (1975). The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton University Press.

Reinvent Albany. (2023). The bill passed – when will it finally land on the governor’s desk? . https://reinventalbany.org/2023/12/the-bill-passed-when-will-it-finally-land-on-the-governors-desk/

Reisman, N. (2023). Hocul’s use of ‘Messages of Necessity’ climbs, speeding up legislative process. Spectrum 1 News. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nys/central-ny/ny-state-of-politics/2023/06/26/hochul-s-use-of–messages-of-necessity–climbs

Roper, D. M. (1974). The governorship in history. Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, 31(3), 16-30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1173206

Slayton, R. A. (2007). Empire statesman: The rise and redemption of Al Smith. The Free Press.

Smith, K. B., & Greenblatt, A. (2022). Governing States and Localities (8th ed.). CQ Press.

Smith, R. N. (2008). The Gangbuster as Governor

Thomas E. Dewey and the Republican New Deal. In C. M. Brooks (Ed.), A Legacy of Leadership (pp. 63-80). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ward, R. A. (2006). New York State Government (2nd, Ed.). Rockefeller Institute Press.

Weeks, G. (1982). A Statehouse Hall of Fame: Ten Outstanding Governors of the Century. State Government, 55(6).

Wildavsky, A. (1969). Rescuing Policy Analysis from PPBS. Public Administration Review, 29(2), 189-202.

Zimmerman, J. F. (2008). The Government and politics of New York State (2nd ed.). SUNY Press.

[1] Alfred E. Smith, Thomas E. Dewey, and Nelson A. Rockefeller

[2] The constitution grants governors ten days upon receipt of a measure to sign or veto the legislation (subject to override by two-thirds of each chamber). When the legislature is in session, unsigned bills become law (i.e., there is no pocket veto); when the legislature is adjourned, the veto period is extended to thirty days and unsigned bills do not become law without the governor’s signature (N.Y. Const. Art. IV. Sect. 7). The legislature may thus shorten the governor’s consideration period by recessing rather than adjourning. When, however, the legislature passes legislation late in the session and adjourns, it grants the governor an absolute veto. The governor has line item veto power over appropriation bills not originally submitted by the executive. Article VII grants the governor to submit an executive budget.

[3] The independent election of the offices of Attorney General, and Comptroller makes these officials rivals for power, particularly in election years. The old saw in New York, is that the acronym AG stands as much for aspiring governor as attorney general. The conflict between the AG and the Governor is very real. On the Spitzer (governor)/Cuomo (AG) conflict, see Confessore, N. (2010, September 23). Spitzer says Cuomo fights dirty. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/24/nyregion/24spitzer.html. Cuomo (governor), in turn, accused AG Letitia James of targeting him because she wanted his job. See Archie, A. (2022). Andrew Cuomo Files a Complaint Against Letitia James for her Sexual Harassment Report. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/09/14/1122894632/andrew-cuomo-letitia-james-new-york ; HBO/MAX. (2023, November 3). Bill Maher Interview with Andrew Cuomo and Melissa De Rosa.

[4] The title of Joseph Persico’s biography – The Imperial Rockefeller — recognizes this extraordinary constitutional power in the hands of a skilled leader. Richard Rosenbaum, a Rochester, NY politician and a member of Rockefeller’s inner circle, explained, “Governor Rockefeller was a supreme user of people. Putting it another way, anybody who wasn’t used by him was disappointed” (quoted in Benjamin & Hurd, 1984, p. 64).

[5] NYS’s 1777 Constitution: “The supreme executive power and authority of this state shall be vested in a governor.”

[6] For a discussion of the republican influence in the revolutionary period, see Pocock, J. G. A. (1975). The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton University Press. On state constitutions drafted during the colonial period, see Countryman, E. (2001). From revolution to statehood (1776-1825): Chapter 13 Never a more total revolution. In M. M. Klein (Ed.), The Empire State: A History of New York (pp. 229-240). Cornell University Press.

[7] Male property holders worth at least £100 could vote for the governor and senators (four-year terms). Adult male freeholders worth at least £20 and rent holders who paid at least 40s, and “freemen” of NYC and Albany could vote for the Assembly [which was elected each year] See Countryman, 2001, p. 239.

[8] This election gamble came into sharp relief when Governor Al Smith, NYS’s reformist and popular four-term Democratic governor and the first Roman Catholic presidential nominee of a major political party, lost his 1928 presidential bid in a landslide to Herbert Hoover in an ugly campaign that brought anti-Catholicism to the fore of national politics. Smith’s opponents circulated photographs of the Holland tunnel, then under construction in NYC, claiming it was a transatlantic passageway to surreptitiously bring the Pope to Washington, DC to run the government with Smith as his puppet Slayton, R. A. (2007). Empire statesman: The rise and redemption of Al Smith. The Free Press.

[9] “They shall be chosen jointly, by the casting by each voter of a single vote applicable to both offices, and the legislature by law shall provide for making such choice in such manner. The respective persons having the highest number of votes cast jointly for them for governor and lieutenant-governor respectively shall be elected.”

[10] While all state constitutions provide for an executive veto and a legislative override, this is the first time Democrats have had a veto-proof majority in both houses since adoption of New York’s current constitution in 1894. The last time this situation occurred was in 1948 when Republicans controlled both houses (Benjamin, 2020).

[11] Ten days (excluding Sundays) for bills sent from January 1 until December 21st, otherwise the bill is considered “pocket-approved.” 30 days (excluding Sundays) for bills sent from December 22nd to December 31st, otherwise the bill is considered “pocket-vetoed” (Reinvent Albany, 2023b) Let’s use a different source – textbook, or the Constitution – RI is just a place saver citation for now.

[12] Excluded from this count: judicial and legislative branches, attorney general, comptroller, and board of election employees.

[13] Van Buren believed in and worked for the development of a two-party system after the Federalists disappeared, leaving a single party: the highly factionalized Democratic Republicans. He was one of the architects of the Second Party System (Democrats and Whigs) and was prescient in his belief that a healthy democracy was predicated on the competition and alternation in power between two major political parties. Executive terms were reduced from three to two years as a measure to make the governor more accountable to the electorate, especially considering the veto and patronage now consolidated in his hands.

[14] There is one important exception to the governor’s appointment authority in the method of appointment to the NYS Board of Regents.

[15] Evers (2013) details how New York governors, particularly Al Smith, used the investigatory power to battle political party machines and their bosses.

[16] Article VII. Governor Smith submitted the first budget prepared under the Executive Budget process in 1928 (a year earlier than required by the state constitution). In 1929, FDR submitted Governor Alfred E. Smith’s budget (New York State Division of the Budget, DOB History, nd. https://www.budget.ny.gov/about-us/history.html#:~:text=Revisions%20to%20Article%20VII%20of,Smith.

[17] Importantly, this clause only applies to actual appropriations. It does not apply to implementing (revenue-raising) budget bills such as proposals for new or increases in taxes and fees.

[18] “Impoundment is the term used to describe the setting aside, in a separate account, of income necessary to pay principal and interest on obligations. The specific method of impoundment — including the timing and amounts — is generally specified by State law for each obligation, and is an integral element of the security behind any obligation.” See NYS Division of the Budget, Glossary https://www.budget.ny.gov/citizen/financial/glossary-all.html#i

[19] Of course, this is not a new idea—it is central to John Kingdon’s multiple streams analysis (MSA) of agenda setting. MSA suggests that policy processes consist of three separate streams: problem, policy, and politics. According to Kingdon, these streams normally operate (fairly) independently of one other but if two, or if especially all three, of them converge or “couple,” a “window of opportunity” or a “policy window” opens that facilitates policy action. But policy windows are normally only open for a short time, so it is crucial that policies are available that have undergone a “softening up” period and can be “removed from the shelf” to “solve” a perceived problem. See Kingdon, J. (2011). Agendas, alternatives and public policies (Updated 2nd ed.). Longman.

[20] N.Y. Const. Article III, Section 25 provides that “Notwithstanding any other provision of this constitution, the legislature…shall have the power and the immediate duty (1) to provide for prompt and temporary succession to the powers and duties of public offices… and (2) to adopt such other measures as may be necessary and proper for ensuring the continuity of governmental operations.” Section 20 defines a disaster to mean “the occurrence or imminent, impending or urgent threat of widespread or severe damage, injury, or loss of life or property from any natural or man-made causes,” providing twenty-six categories of qualifying natural and man-made events.

[21] Under Section 29-A: “Subject to the state constitution, the federal constitution and federal statutes and regulations, the governor may by executive order temporarily suspend specific provisions of any statute, local law, ordinance, or orders, rules or regulations, or parts thereof, of any agency during a state disaster emergency, if compliance with such provisions would prevent, hinder, or delay action necessary to cope with the disaster.”

Suggested Citation: Buonanno, L. and L. Parshall (2024). New York State’s Executive. Governing New York State Through Crises Project (July 29). https://governingnewyork.com/new-york-states-executive/